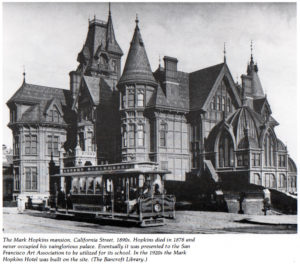

In FORGIVEN, after Kula’s rude introduction to San Francisco’s meaner streets (as described in my last post), she finds her way  to the home of her future benefactor. Here’s how she describes it: “Turrets and towers, porches and balconies…these only began to describe what looked like a confection of furbelows and curlicues and fancies.”

to the home of her future benefactor. Here’s how she describes it: “Turrets and towers, porches and balconies…these only began to describe what looked like a confection of furbelows and curlicues and fancies.”

Before the earthquake and fire of 1906 San Francisco was a city of opposites. We’ve had a glimpse at the lower rung of society’s ladder; now let’s take a look at how the upper one percent lived.

The wealthy entrepreneurs of California made their money in mining and the railroad. After the gold strike at Sutter’s Mill, as San Francisco was a bustling and somewhat primitive seaport, the wealthy escaped the noise and smells by settling the hills above the nascent city. The most spectacular mansions of the period were built on the hill nicknamed “Nob”, after the nobs or “nabobs” who built those mansions. Most famous of these nobs were the “big four” railroad magnates: Ch arles Crocker, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins and Collis Huntington. Other wealthy families followed in their wake.

arles Crocker, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins and Collis Huntington. Other wealthy families followed in their wake.

The mansions were so lavish that Robert Louis Stevenson dubbed Nob Hill the “hill of palaces”. Stanford’s residence was described as having twenty-five sleeping compartments on the second floor, and the main entrance was a rotunda surrounded by sixteen Corinthian columns. Ornamental artwork decorated the walls and ceilings, and the artist, Mr. G. G. Gariboldi, “was given carte blanche,” to quote an article from the Daily Alta California of April 7, 1876. The article continues with a description of four of the ceiling panels: “finished with emblematic figures personifying “Fine Arts,” “Mechanics,” “Agriculture” and “Literature.” The motive of this decoration of the rotunda was doubtless to present the documentary and historic character of Italian art.”

Then there was the Crocker mansion. Crocker’s neighbor, a poor undertaker, Nicholas Yung, refused to sell his house and lot to Crocker when the magnate bought the rest of the block around. Out of anger, Crocker built at great expense a three-story tall fence that surrounded Yung’s house and completely blocked out the sun for the Yungs. The “Spite Fence” remained in place for thirty years, until 1904.

All this extravagance, with the exception of silver baron James Flood’s mansion, was completely destroyed by the 1906 earthquake, which leveled not only these “palaces”, but also the decadence of the Barbary Coast. More on that to come.

These wealthy patrons of the arts would have been familiar with the subject of my next post, Enrico Caruso.

r Nob Hill, so named after the rich “nabobs” or “nobs” who built large mansions there. Cable cars, an 1873 invention of Scots immigrant and mechanical engineer Andrew Smith Hallidie, connected the growing neighborhoods and steep hills in this “Paris of the west”.

r Nob Hill, so named after the rich “nabobs” or “nobs” who built large mansions there. Cable cars, an 1873 invention of Scots immigrant and mechanical engineer Andrew Smith Hallidie, connected the growing neighborhoods and steep hills in this “Paris of the west”.

I had known some things about him, this man I never met. I knew he’d run off at some point after losing his job when my mom was twelve, going to live with his sister in Atlanta. I did not know what he looked like, have still never seen a picture. I did not know what he did for a living before he was unemployed. I did not know that he had hung himself in his sister’s closet.

I had known some things about him, this man I never met. I knew he’d run off at some point after losing his job when my mom was twelve, going to live with his sister in Atlanta. I did not know what he looked like, have still never seen a picture. I did not know what he did for a living before he was unemployed. I did not know that he had hung himself in his sister’s closet. e. The logical one. The one with plans. And so when Paris goes missing one night in Vegas where they live, leaving behind a string of increasingly upsetting clues, Leo finds herself on a scavenger hunt/road trip she never asked for. She finds herself taking help from a boy named Max even though Leo is not one to ask for help and certainly not one to ask for help from boys she doesn’t know. Is Paris in trouble, really? Is she just screwing with Leo for reasons unknown? Or is the situation more subtle than that? I wanted to explore those moments when we’re pushed to the wall and still aren’t quite sure what to do, where our blind spots for those we love, keep us from seeing –or facing—the truth.

e. The logical one. The one with plans. And so when Paris goes missing one night in Vegas where they live, leaving behind a string of increasingly upsetting clues, Leo finds herself on a scavenger hunt/road trip she never asked for. She finds herself taking help from a boy named Max even though Leo is not one to ask for help and certainly not one to ask for help from boys she doesn’t know. Is Paris in trouble, really? Is she just screwing with Leo for reasons unknown? Or is the situation more subtle than that? I wanted to explore those moments when we’re pushed to the wall and still aren’t quite sure what to do, where our blind spots for those we love, keep us from seeing –or facing—the truth.