I’m a fan of Steven Pressfield. He’s a screenwriter who also shares his substantial knowledge of craft, and I’ve been following him for a long time. A while back he wrote this post about the villain (antagonist).

At the time I wanted to argue with him in the same way he argued with his former mentor. After all, I thought, we really do want to make our villains nuanced and complex. We want them to have backstories and maybe even hint at redemption. How can they not change?

And then I realized that Pressfield was right.

Story is About Change

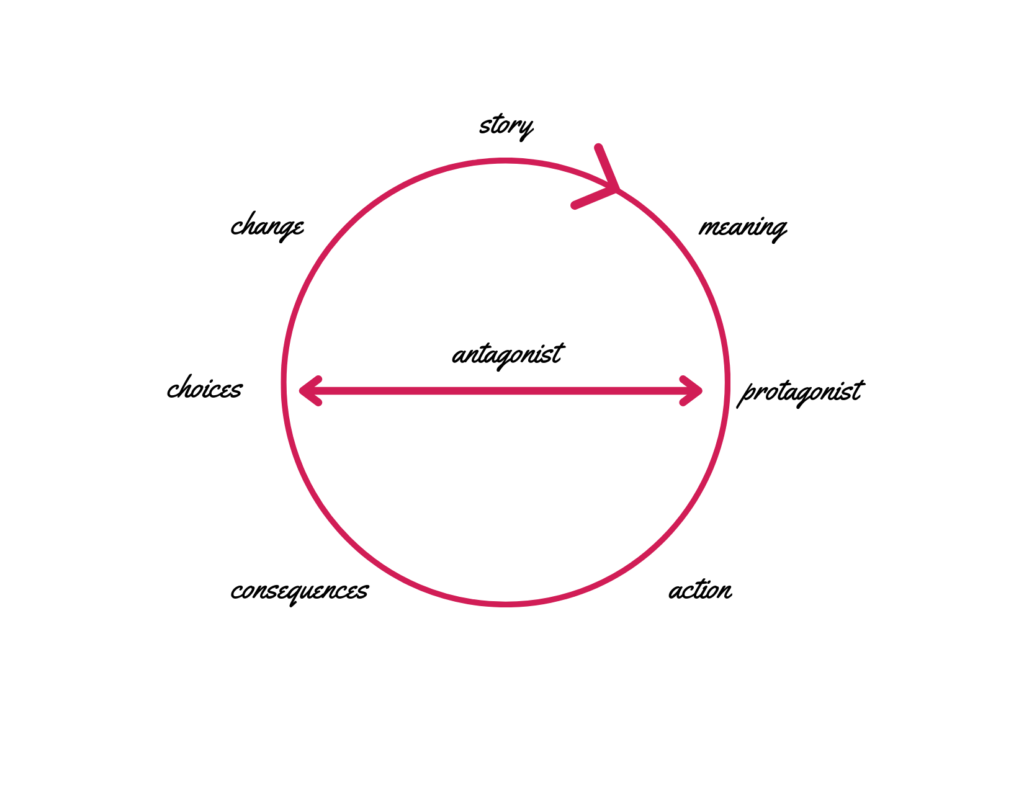

In constructing my upcoming introductory course, I was going through the arc of change in plot, and created this linking thought:

Stories must have meaning.

Meaning is what matters to the protagonist.

The protagonist must act.

Actions must have consequences.

Consequences lead to change.

Due to pressures by the antagonist,

and choices of the protagonist,

the protagonist changes over the arc of story.

And then I wanted to diagram this chain for my students, so I made this:

When I was wondering where to put the antagonist, I realized that they occupy a spot between the protagonist and “change” and the choices leading to change, as in, the antagonist is in opposition to the changes that the protagonist must make through choices to his/her/their life.

Whoa.

It was suddenly clear that the antagonist’s role is quite simple – even when the antagonist’s character is made complex by wounding, or sympathetic tendencies, or however you want to deepen their character. That simple role is the antithesis of change.

We cannot deepen the antagonist’s character by making them change or they will become the hero.

Here’s a For-Instance Argument

My talented son is writing an epic science fiction series (check them out – they are amazing). Several of his novels depict characters in opposition, and some turn the tables on the reader by making the villain of one the main character or hero of the next. This leads to ambiguity, but not to confusion because…

…the real villain in all his stories is war. His novels and short stories are a testament to the horrors and idiocies of war.

His characters all experience an arc of change, but war? War is always terrible.

Check your own story for your antagonist. Make sure that they do not change, at least not in the course of that single narrative arc.

Want to know more about any of my coaching packages or my upcoming courses? Sign up here:

Thank you, Janet, for recommending the Pressfield article. Like you, I wanted to argue against the theory for the same reason you gave. But now I’m shaking my head in agreement. Villains can be nuanced, but ultimately, they don’t change their minds.

You’re welcome and it was a shock to me, too – but it’s so clear now! Thanks once again for commenting!!