The previous post discussed the radicalism that grew in the 20s. Here’s something else altogether:

Calling All Ghosts: Ouija Boards, Spiritualism, and Harry Houdini

One of the central images of SIRENS is that of ghosts and spirits and magic. I found this facet of the 1920s by accident, but it fit so perfectly into the novel I couldn’t ignore it. Cue the spooky music…

Maybe it was the war, maybe it was the influenza outbreak, but people in the 1920s became obsessed with life after death.

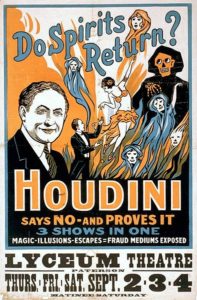

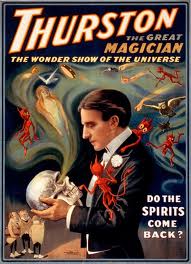

There were (well, yeah, there still are) two camps: those who believed in life after, and those who didn’t. Harry Houdini didn’t. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Howard Thurston did.

Houdini and Thurston were both magicians, so they knew how to pull the wool over someone’s eyes. Doyle – Mr. Sherlock Holmes – knew how to uncover secrets. These three were all good friends, and they argued this point excessively. Were there spirits? Ghosts? Was there life after death? Who could prove the point?

Two of the popular parlor games of the 1920s were séances and Ouija boards. Both of these purported to channel the dead through a medium, in the case of a séance, or through the group emotions, in the case of a Ouija board (if you’ve never played with the latter, it’s kind of fun. But you have to suspend your disbelief. That makes it spooky.) The dead would send, through these media, obscure messages back to the living.

Magic shows were a public phenomenon of the 1920s, and two of the greatest magicians were Harry Houdini and Howard Thurston. Houdini was a skeptic: he knew how to make people think one thing, but “it was all a trick. Fakery.” Thurston, too, was an excellent magician, but he actually believed that there was something guiding him, a kind of spirit life. The two engaged in a friendly competition, culminating with a wager that the one who died first would haunt the other.

Thurston’s shows were all about spiritualism. He would make a girl float magically in the air; he would make a girl vanish altogether; he would call forth floating apparitions to “speak.” His illusions were some of the best and his popularity high. But Houdini’s renown was greater, due to his amazing performances in escaping dire circumstances. And Houdini’s premature death of peritonitis gave a legendary aspect to his name, since the secrets of his magic act – ironically – went with him to the grave.

Thurston lived on but his magic shows were supplanted by a new public fixation: the moving picture.

As the decade progressed and Americans forgot their heartbreak over the war and their losses during the flu pandemic, and became more and more obsessed with the “new” things – cosmetics, automobiles, wealth, and glamour – preoccupation with spirits slipped away. They didn’t know it, but at the end of the 1920s Americans would bump up against a whole different kind of haunting experience: the Depression.